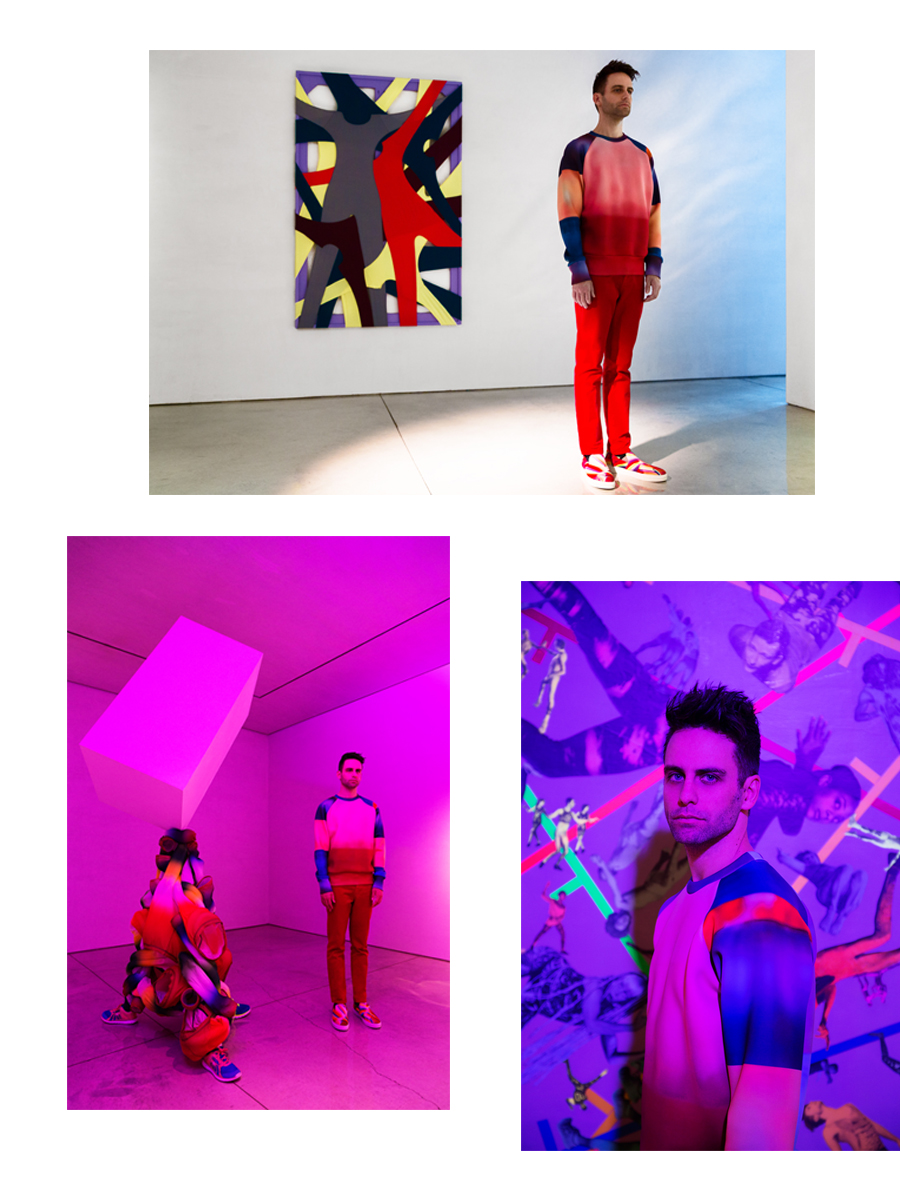

My first foray into styling an artist in his surround, Ryan McNamara graciously allowed me to shoot him within his show Gently Used at Mary Boone Gallery. I became enamored with Ryan after seeing his performance piece at Art Basel, MEEM 4 Miami: A Story Ballet About the Internet. A rare moment where I was completely taken out of my head and entranced by the isolated movements that were happening around me. Here at Mary Boone he has again enhanced the idea of slippage between audience and performer by activating the viewer experience in a play on the unexpected. We delve deeper with him here.

PD: The internet has changed our behavior in many ways including our brain function which has rewired itself to adapt to the mode of the internet, ultimately shortening our attention span. In your recent performance MEEM 4 Miami: A Story Ballet About the Internet you explore our current condition, mimicking the way information is transmitted, while simulating our A.D.D. by physically moving the audience around the theatre, disrupting continuity and providing multiple sources of stimulation. Can you talk a little about your thoughts on the internet and its psychological impact on the viewer? How does this influence the ways you interact with an audience?

RM: I think it may be a misconception, or just some pop sociology, that states that our “attention spans”—which is indeed a term that we take for granted—have gotten shorter. When I was growing up, there was a lot of noise on morning news programs and in magazines about the MTV generation and how their “attention spans” were being massacred by mass media. But they were talking about me, a person who was glued to MTV for hours and hours. It was one-directional attention, though. Now the call for attention has been dispersed. It’s multidirectional. But I’m still paying attention.

PD: Do you have a different set of expectations of the audience when the venue is a gallery space and the exhibition consists of static objects?

RM: I don’t expect anything of the audience. I’m just happy they showed up.

PD: I read that you often have no more than a few weeks to prepare a performance piece. With a scheduled gallery exhibition time lines change. How does your creative process differ when you have more time?

RM: Having the luxury of time obviously has its perks, namely more sleep. But there is a certain surge that accompanies a short lead time. It doesn’t give my anxiety a chance to pilfer my energy away from creating. Actually, who am I kidding. I live in a constant state of anxiety no matter what.

PD: Is there a big difference between performance and object making for you?

RM: For my show at Mary Boone, I treated the props, stills and ephemera from past projects as raw material to create new work. One of the biggest lies in contemporary art is this idea that performance is ephemeral. I had this idea that while the props and costumes were sitting inactive in bins, they desired to create their own performances. They don’t pay attention to the distinction between my different performances, so there are props from one performance that are overlaid with images from another. I looked at the images and props and costumes as raw materials, attempting to see them with fresh eyes, as if I’m excavating a site.

PD: In your past gallery exhibitions the viewer was involved in the production of the show or expected to participate in the exhibition in some way. How did you approach this show?

RM: I wanted to create a situation in which the pieces felt like they were performing as “art works.” I thought this may bring to the viewers’ minds the ways in which they are performing “audience.”

PD: When I first walked into Mary Boone everything was very still. Every sculpture, collage and painting was placed carefully within the gallery. Then all of a sudden the lighting changed. The stage lights, which I hadn’t noticed up until that moment, flashed sporadically casting subtle shadows that moved quickly across the wall. It gave an eerie feeling of another presence in the room. Then I noticed pieces of cyber technology incorporated into the work, and I realize that perhaps I was the one being watched. There is something a little bit sinister about all of this. Can you talk about that?

RM: I timed the light movements to be subtle, perhaps the viewer only sees them out of the corner of her eye. Not actually registering what happened, just that the sense of movement in what seemed to be a static room. In a way it mirrors the history of these objects; the ghosts of performances past. The spotlight is never fixed.

PD: The moving lights and shadows also had the effect of heightening my senses; I heard the ambient noise coming from the gallery office: ringing telephones, muted voices, foot steps etc. I was hearing what was “off stage”. The whole gallery had become a setting like a fun house in a carnival. I wondered if you had intentionally incorporated what was off stage into the work on stage. The ambient noise felt like it was part of the exhibition. Was this intentional? Or just a great side effect of the experience?

RM: As John Cage’s 4’33” taught us, the coughs and rustling of the audience are as much a part of the piece as the music. I’m interested in gestures that make you aware of the specificity of the space you are inhabiting. The sparseness of the gallery heightens this—all audio and visual shifts are magnified.

PD: In the past you’ve talked about the nature of performance being subversive. While an artist is performing there is an inadvertent transfer of power from the institution to the artist. The artist has complete control over what will happen and in that moment the institution becomes passive and anything can occur. I love that idea. It creates a great deal of suspense. In your current exhibition there are many elements that get upended, in some cases literally, like the billowing mass of body suits bolstering a plinth, turning the sculpture/plinth relationship on its head. You invert the nature of the Art/Viewer relationship in the show as well, where the viewer eventually realizes she is being watched, or is on stage as much as the Art itself. Do you think of yourself as a subversive artist?

RM: I’ve had a lot of conversations recently about what it would mean to be a subversive artist today. Institutions have rapidly decreased the delay between the birth of a counterculture and when they consume it, so much so that it seems silly to even use the term “counterculture” anymore. So how does someone subvert something that is welcoming her with open arms? This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I like a lot of institutions.

PD: Overall there is something vulnerable about this exhibition, especially about the sculptures that are contorted, splayed, and suspended. They are anthropomorphic forms that seem to lack physical control. Although the work is also laced with humor and surprise, at its core it feels like you are exploring the idea of power or perhaps a lack of power. Is this fair to say?

RM: It reminds me of performance. As the performer, you have the power in the situation—the audience is submissive to your actions. But the performer’s craving of approval and appreciation upends that power dynamic. In the same way these pieces crave your approval.

Hagahi sweatshirt, Christopher Kane pants, Christopher Kane sneakers

Mary Boone Gallery, Ryan McNamara, Gently Used

Hair by Cosma De Marinis, Photographs by Tylor Hou